Cops lie to suspects during interrogations. Should detectives stick to the truth?

Thomas Perez Jr. was hours into an interrogation by police about his missing father when they dropped some devastating news: A body had been found.

Thomas Perez Sr., they told his son, was dead.

The news crushed Perez, but he never considered that the authorities could be lying.

They were. The tale of his father on a gurney in the morgue was a deception used to push Perez to confess to killing him.

Over several more hours, interview transcripts show, detectives shut Perez down when, again and again, he told them he hadn’t harmed anyone. Instead, they hammered him with accusations. Exhausted, in despair and desperate to stop the “pounding,” Perez said later, he finally agreed with police that he had killed his father.

Then, he tried to hang himself using a shoelace — hours before his father was located, alive and well.

“They were not listening to me telling them the truth,” Perez told Times reporters recently, trying to explain why he would falsely confess. “Their continual attack on me came to the point where I no longer wanted to tolerate it. I felt, ‘I have to end this.’”

Thomas Perez Jr. falsely confessed to killing his father after a 17-hour interrogation by Fontana police during which they lied about their evidence and told him his dog would be euthanized.

(Fontana Police Department via Law Office of Jerry L. Steering)

In their push to break down a man they suspected of being a killer, Fontana officers were drawing on the playbook of a combative and sometimes deceptive interrogation philosophy that has been widely embraced by police departments across the country for almost 80 years. It is a method that trains detectives to pursue a confession and be unrelenting in their questioning when they believe they have the guilty suspect, and even lie about evidence.

The method is so widespread that it has been glamorized in film and TV procedurals such as “Law and Order”: a tough and driven detective goes into “the box,” as interrogation rooms are sometimes called, and obtains a confession from a suspect through trickery or sheer force of will. Some policing experts say that, properly used, the method can elicit truth from criminals who are lying.

But increasingly, critics and criminal justice experts — including both law enforcement leaders and civil rights advocates — have raised concerns that the method, especially if deployed irresponsibly or to excess, can lead to false confessions and fabricated testimony, putting the wrong person behind bars and leaving criminals free to commit more crimes. In recent years, some experts have been pushing a newer method of interviewing suspects, developed by intelligence services in the wake of the 911 terrorist attacks, that discourages lying to suspects and focuses on gaining information and building rapport.

“There is no question in my mind that there are innocent people sitting in prison, based on the approach the law enforcement took,” said retired Los Angeles Police Department Det. Tim Marcia, who helped the LAPD’s elite Robbery-Homicide Division adopt more modern methods of interrogation.

A 2003 photo of Los Angeles Police Department Dets. Rick Jackson, left, and Tim Marcia unpacking evidence related to a 20–year–old murder case.

(Los Angeles Times)

About 13% of exonerations since 1989 — totaling 458 people — have involved false confessions, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, a project of UC Irvine, University of Michigan Law School and Michigan State University College of Law. One 2016 study by the Innocence Project found that about 50% of the time, the real culprits in those crimes were later located through DNA, and had gone on to collectively commit an additional 142 violent crimes.

Amid concerns about the practice, the California Legislature in 2021 passed a law requiring all training for investigators be science-based methods. The law was vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, who noted the potential costs to the state of making such training mandatory.

Now, lacking that mandate, there is a culture war within California law enforcement about how suspects should be interrogated. Some have embraced the new approach, among them El Dorado County Dist. Atty. Vern Pierson, who helped write the vetoed legislation. “It’s ethical and more effective,” he said.

Others say police, when faced with lying criminals out to do harm, must sometimes lie and pressure them in the interests of public safety.

“There are times where it’s extremely valuable to solve crimes and to, you know, get to the end of a case,” said Fontana Police Chief Michael Dorsey.

Fontana recently paid Perez $900,000 to settle a lawsuit he filed against the department over the 2018 episode, and Dorsey said that his department has instituted some changes in the wake of the Perez case.

But telling officers not to lie during interrogations is not among them.

For a year, The Times has investigated this divide around interrogations, examining methods as well as multiple cases involving false confessions.

Part One: The wrong guy

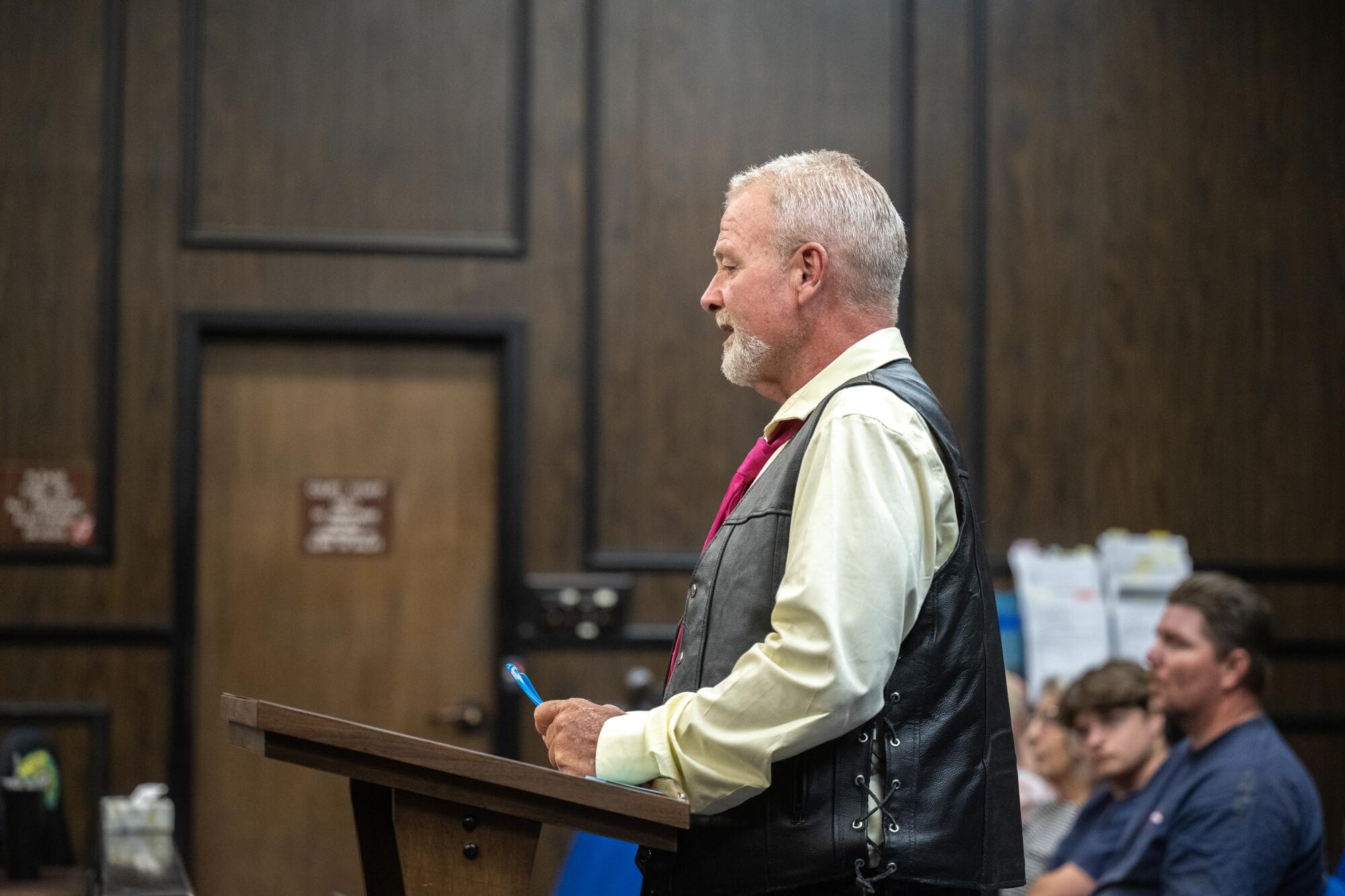

El Dorado County Dist. Atty. Vern Pierson has become a leading critic of commonly used police interrogation tactics he believes can lead to false confessions.

(Max Whittaker / For The Times)

Pierson, the El Dorado County D.A., is in some respects about as far from a progressive prosecutor as it is possible to be. A former expert marksman in the Army, he is a conservative Republican elected in a deep red county and an author of Proposition 36, the new “tough on crime” law California voters approved last November.

When he took office in 2007, Pierson was skeptical of reform advocates, such as the Innocence Project, that claimed there were untold numbers of people wrongly locked up in prisons around the country.

“I kind of have a love-hate relationship with the Innocence Project,” he said. “I appreciate what they do. … But on the other hand, I think sometimes, oftentimes, you know, they’re representing people who are factually guilty.”

Then, he discovered his office had locked up someone for murder who was, in fact, innocent.

After an investigation prompted by the Northern California Innocence Project, Pierson in 2020 asked the court to exonerate Ricky Davis, who had been convicted of the 1985 murder of Jane Hylton, a newspaper columnist. In 2022, Pierson convicted another man, Michael Green, for her murder, based on new DNA evidence.

Ricky Davis addresses the court at the 2024 exoneration hearing of Connie Dahl. Davis and Dahl were wrongfully convicted of a 1985 murder after Dahl provided a false confession.

(Jose Luis Villegas / For the Times)

Earlier this year, Pierson also posthumously exonerated Connie Dahl, who falsely confessed to helping Davis carry out the crime, pleaded guilty to manslaughter and died in 2014 after helping to convict Davis.

The experience affected Pierson profoundly. He became convinced that Dahl had broken under the relentless questioning of detectives who had been trained to use deception and aggressively pursue confessions once they had identified a suspect. Detectives had falsely told Dahl there was physical evidence linking her to the crime.

Pierson personally went to Davis’ cell to tell him he was being freed, and promised Davis he would work to make sure others were not convicted with false confessions gleaned from “guilt-presumptive” interrogations that assumed from the start that detectives had the right person.

“I told him, I’m going to change the way law enforcement is trained, and the way detectives, specifically, do interviews and interrogations,” Pierson recalls. “And I, you know, I intend to do that.”

But as Pierson would discover, like many reformers before him, that meant changing a mindset that has been entrenched for generations.

Part Two: The third degree

A 1925 photo of prosecutor Buron Fitts, left. As L.A. County’s district attorney from 1928 to 1940, Fitts presided over cases in which defendants later said they had confessed after investigators beat them.

(Los Angeles Times)

In the first decades of the 20th century, police officers across the country had an astonishingly effective method of getting suspects they believed guilty of certain crimes to confess.

It was known as “the third degree” and involved tactics that today would be considered torture: brutal beatings; deprivation of food, water, sleep and toilets; prolonged confinement. Despite being illegal, the approach was widespread, according to a 1931 report from the federal Department of Justice. That report, as U.S. Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren would later point out, also cautioned that the method “involves also the dangers of false confessions” and “tends to make police and prosecutors less zealous in the search for objective evidence.”

But no one could say it didn’t work: In some departments, police were clearing huge numbers of homicides.

Still, eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court put a stop to it. In 1936, the court found, in Brown vs. Mississippi, that confessions obtained by use of torture would not be admissible in court. Four years later, in Chambers vs. Florida, the court tossed confessions made after interrogations under “circumstances calculated to inspire terror.”

The message got through to law enforcement agencies across the country: Infliction of physical pain and duress was out. But it left many detectives with a pressing question: How were they supposed to solve crimes going forward?

John Reid, a former Chicago police officer and polygraph expert, and Fred E. Inbau, a criminologist and former director of Northwestern Law School’s Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory, had an answer.

Rather than beat people suspected of crimes until they confessed, the two developed an interrogation method designed to get people to talk without laying a finger on them.

The Reid Technique, as it came to be known, relies on insights from behavioral science to help police officers determine if a suspect is likely guilty, or if a witness is telling the truth. The three basic steps are to gather evidence; talk to those involved in non-confrontational, fact-gathering interviews; then interrogate those suspected of guilt.

The interrogation is meant to leave a suspect little room to lie or evade, and detectives are taught that they should do the majority of the talking, according to Joseph Buckley, president of John E. Reid and Associates, the for-profit company that provides training in the method. While investigators are told not to falsely offer leniency, they are taught to present moral or psychological justifications for crimes that could work to put the subject at ease.

“In most instances, it’s easier for someone to acknowledge that they’ve done something if, in their mind, they can kind of minimize their culpability,” Buckley said.

You committed the crime — but you had a good reason to do it, the detective might say, for example. A child molester might be told that the victim looked older, or that the investigator, too, finds the child to be attractive.

“The core of the Reid interrogation process is ‘theme development,’ in which the investigator presents a moral or psychological excuse for the subject’s behavior. The interrogation theme reinforces the subject’s rationalizations or justifications for committing the crime,” Reid and Associates explains in a bulletin titled “Common Erroneous and False Statements About the Reid Technique.”

The Reid Technique also condones lying in certain circumstances, as long as it doesn’t involve “incontrovertible or dispositive evidence,” noting that the Supreme Court in 1969 in Frazier vs. Cupp ruled that police lying to a suspect did not make an “otherwise voluntary confession inadmissible.”

Reid trainings were soon used by police departments across the country. Quickly, competitors tweaked the method and opened their own training companies based on similar principles. Today, there are many companies across the U.S. that teach a version of interrogations that includes deception and the notion that, with proper training, officers can detect when someone is lying.

A 2004 photo of Washington D.C. Metro Police Det. Jim Trainum.

(James M. Thresher / Getty Images)

“It does work,” said retired Washington D.C. Metro Police Det. Jim Trainum, who said he embraced the approach when he became a homicide detective in the 1990s after buying and studying a book Reid and Inbau wrote together, “Criminal Interrogation and Confessions.”

But Trainum said he soon discovered something else. The method, he said, “works too well.”

Trainum has since retired and authored his own book: “How the Police Generate False Confessions: An Inside Look at the Interrogation Room.” He recounted a case he worked in the 1990s, when a man was found savagely beaten to death by the banks of the Anacostia River. The man had been robbed, and his credit card had been used all over town.

Police had a composite sketch of the person using the card, and after it was circulated, a tip led them to a 19-year-old woman living in a homeless shelter. Police obtained samples of her handwriting, and went to a handwriting expert, who declared them to be a match to receipt signatures for charges on the dead man’s credit card.

During the first hours of her interrogation, the woman denied all knowledge of the crime. Trainum, unrelenting, continued to deploy tactics he believed would get to the truth.

Finally, Trainum recounted, “she tells us that, ‘you’re right. I signed the credit card slips.’”

A breakthrough.

The detectives kept at her. After 17 hours, she had confessed that she knew the dead man. He had abused her. So she and some friends had abducted and beaten him. The woman, who had a baby back at the homeless shelter she was anxious to return to, said she hadn’t meant for him to die.

She was charged with murder and locked up — away from her baby — to await trial.

Then she recanted.

Trumain decided to gather more evidence against her. He went to the homeless shelter where she lived — which had a strict sign in/sign out policy — to get its logs, to prove she was out at the time of the man’s abduction and during the times she had used his credit card.

Papers in hand, he said, he was driving back to the station when he started to glance through them. “I about wrecked the car,” he said. “According to that [log] book, there was no way she could have committed that murder.”

In confusion, Trumain went to a second handwriting expert, this one at the FBI, to make sure that evidence, at least, would hold up. Another nasty surprise: The FBI’s expert said the handwriting didn’t match.

At that point, Trumain realized he had overlooked something big: The woman had an infant. This meant she would have been seven months pregnant at the time of the murder. The suspect they were looking for had not appeared pregnant at all.

He had locked up the wrong person.

(The woman later told the radio program “This American Life” that she had confessed because she was exhausted, police weren’t listening to her and if she told them something, perhaps they would let her go home.)

Trainum was shaken. “I feel bad,” he said. “But I feel confused. Why would she have confessed?”

Buckley, the president of Reid & Associates, said he is not familiar with the details of Trainum’s case, but that in most instances of false confessions he has examined, investigators have not followed best practices.

“It’s usually that they’re engaging in inappropriate behaviors that the courts have long deemed to be coercive,” Buckley said.

Part Three: Why do innocent people confess?

Still, the question of why innocent people confess was coming up more and more often in the 1990s, after the introduction of forensic DNA testing that provided hard evidence of innocence or guilt.

The first DNA exoneration happened in 1989, freeing a Chicago man in prison for a rape that never occurred. The alleged teenage victim, frightened that her parents might discover she was sexually active, later admitted she had fabricated the story. After that, DNA exonerations became almost common, and startling similarities between the cases began to emerge.

Richard Leo, a law professor at the University of San Francisco and a leading expert on the topic, said “police-induced false confessions are a leading cause of wrongful conviction of the innocent.”

Though about a quarter of DNA exonerations involve a false confession, that percentage jumps to more than 34% for those who were under 18 when wrongfully convicted, and 69% for those with mental disabilities, according a 2022 analysis by the National Registry of Exonerations.

The percentage of wrongful convictions that include false confessions also leaped when the crime was a homicide. Sixty percent of wrongful convictions for people found guilty of homicide involved a false confession, according to Saul Kassin, the author of the 2022 book “Duped: Why Innocent People Confess and Why We Believe Their Confessions.”

One early study in 2004 found that 84% of documented false confessions happened when interrogations lasted longer than six hours.

That was a factor in one of the most notorious false confession cases, that of the Central Park Five, now known as the Exonerated Five.

In 1989, in a crime that transfixed New York City, five teenagers, Black and Hispanic, were convicted of participating in a violent assault on a jogger in Central Park. All five were interrogated for hours by detectives and ultimately implicated themselves. They recanted, but it was too late. They were convicted and spent years in prison before a confession by the real perpetrator and DNA evidence proved they had not been involved in the crime.

“When we were arrested, the police deprived us of food, drink or sleep for more than 24 hours,” one of the five, Yusef Salaam, now a member of the New York City Council, wrote in 2016 in the Washington Post. “Under duress, we falsely confessed.”

After spending 17 years behind bars for a murder he did not commit, Lombardo Palacios walks out of the Los Angeles County courthouse a free man with his mother, Claudia Ortiz.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

The cases aren’t just historical. Last week, Lombardo Palacios and his co-defendant, Charlotte Pleytez, had their murder convictions thrown out by a Los Angeles judge at the request of Los Angeles County Dist. Attn. Nathan Hochman. At 15, after an hours-long interrogation, Palacios falsely confessed to involvement in a 2007 gang shooting in Hollywood. He recanted his statement, but it wasn’t until a private investigator recently tracked down other suspects that the case was reopened. They were released this month after 17 years of incarceration.

Despite growing concern from social justice activists and defense teams about guilt-presumptive methods of questioning, serious concerns about interrogation techniques weren’t raised by those conducting them until about 2005, after the Washington Post reported that the United States was holding terror suspects in secret overseas prisons where torture was used.

By the time Barack Obama won the White House in 2008, there was momentum not only to repudiate the use of torture by U.S. intelligence agencies, but also to embrace new methods that were deemed more ethical and reliable. In August 2009, Obama ordered the creation of the cross-agency High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group, or HIG. Along with handling the interrogation of terror suspects, the HIG was charged with creating best practices for interrogations.

Other countries had already moved away from combative interrogations in their civilian policing. In the 1990s, England and Wales, under pressure over coerced confessions, had pioneered an interrogation method that forbids lying and relies on open-ended questioning. In ensuing years, lying by police would be outlawed in other European countries, Japan and Australia. The HIG studied those models, then created its own protocols.

One of HIG’s early partners in turning research into methods was the LAPD’s Robbery-Homicide Division. The LAPD in 2012 sent two homicide detectives to HIG training: Marcia and colleague Gregory Stearns.

Stearns said in a recent interview that one day in the class convinced him of its value.

LAPD Det. Gregory Stearns at police headquarters in downtown Los Angeles.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

“I bought into it right away,” he said. Beyond the open-ended questions, he saw how the techniques encouraged investigators to prepare for interviews, rather than relying on spur-of-the-moment intuition or tricks.

“That’s the thing that really struck me at first,” he said. “Sometimes we’ll spend weeks, months, years, investigating things like homicides, and then if the moment comes when you’re actually going to be interviewing a suspect, you know, how much time did you really spend getting ready for that?”

The new ideas, he said, backed by scientific proof that they were effective, were “really knocking down a lot of the myths that have been passed down to generations of investigators.”

Marcia worked with HIG to use the LAPD’s Robbery-Homicide Division as a laboratory to study the methods further.

Part Four: The culture war

The approach has been slower to take hold across law enforcement in general.

Still, as evidence mounted that some groups — including young people and people with mental disabilities — were more susceptible to false confessions, legislators began to take notice.

States began to pass laws outlawing the use of psychological pressure or lies in interrogations of minors, starting with Illinois in 2021. California followed suit with legislation, passed in 2022, that took effect last January.

Supporters of that bill argued that “law enforcement’s use of deceptive interrogation methods, such as threats, physical harm, deception, or psychologically manipulative tactics … create an incredibly high risk for eliciting a false confession from anyone, and particularly youth.”

“We could be unfairly interrogating people in parts of our state, and I think that is wrong,” former state Sen. Bill Dodd (D-Napa), said of his push to make training in new techniques mandatory.

(Rich Pedroncelli / Associated Press)

Then-state Sen. Bill Dodd had also attempted to curtail those types of interrogation methods across the board with 2021 legislation that would have made training in new techniques the mandatory requirement moving forward. Newsom, noting the costs, vetoed Dodd’s bill and instead instructed the Commission on Police Officer Standards and Training, commonly known as POST, to develop optional classes.

Undeterred, Pierson has continued to wage his campaign. POST has made the new evidence-based method standard training for detectives who come through its programs. And many training companies operating in California now advise against long interrogations and a reliance on lying and manipulation — though lying still remains a tactic police are allowed to use.

But changing how detectives work inside interrogation rooms is a tougher task, many policing experts said.

The Dodd bill was opposed by the California Statewide Law Enforcement Assn., which represents investigators in a number of state agencies.

“This legislation goes too far by prohibiting the use of long-standing interrogation practices, which are only used when an investigator is reasonably certain of the suspect’s involvement ,” the association wrote in its formal comments.

It added that “by limiting the scope” of what investigators can say in the interrogation room, “investigations will grind to a halt.”

Dennis Gomez, a retired police lieutenant from the city of Orange who recently took over California’s Behavior Analysis Training Institute, a private company that trains police officers how to question people, said he is familiar with the sentiment.

“It is a culture,” he said. “And it is so hard to change that.”

He said some detectives come to his courses resistant to the idea that they can solve cases without the tools of lying and pressure many have relied upon for years.

“In the early part of the week, they say, ‘This is ridiculous. How are we ever going to get a confession,’” he said.

But after the course is finished, Gomez said, detectives often tell him they wish they could have learned the newer methods sooner.

Andrew Mendosa, who oversees interviewing and interrogation training for POST, called losing the ability to lie about facts and evidence many officers’ “biggest fear.” But Mendosa said that many detectives eventually realize that if they prepare for interviews with suspects by gathering evidence, and take a holistic approach, they don’t need to lie to them. Mendosa said he was confident that the new interrogation methods would eventually be adopted across California, though it may take a generational shift.

Pierson wants the state to be more proactive in making training mandatory, and he doesn’t accept the governor’s reasoning that it would cost too much.

“I know that a single false confession leading to a conviction is going to cost taxpayers more,” he said.

He points to one study that shows California spent more than $200 million between 1989 and 2012 because of wrongful convictions, a sum tied to more than 2,100 years of time spent behind bars by innocent people.

Dodd, the former state senator, also questions leaving the decision on training to California’s hundreds of law enforcement departments. “If the sheriff in your unit doesn’t believe in this and doesn’t send you to be trained, then you don’t get trained,” he said. “We could be unfairly interrogating people in parts of our state, and I think that is wrong.”

In Fontana, Police Chief Dorsey said the Perez case had sparked some changes internally as the department has sought to use the debacle “as an opportunity to be better.”

For example, he said, the department has ramped up mental health training and launched a collaboration with San Bernardino’s Behavioral Health Department. He also said that the length of time that police officers interrogated Perez was “excessive.”

But Dorsey said he did not conclude from the episode that lying to suspects during interrogations is always problematic. The two detectives, he said, “were truly out just trying to do the best they could” and had reason to believe, based on their assessment of the Perez home, that a violent crime had occurred.

“Were they perfect? No,” he said. But, “we’ve used this as an opportunity to be better.”

And while he called the debate over interrogation methods a “complex question,” he said he remains convinced “that there’s a point in time to use ruses in interrogation techniques.”

“I don’t want any contact, ever, with any police officer,” Thomas Perez Jr., left, says of his lost faith in law enforcement. “I see a police car, I look the other way.”

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

More than five years after his ordeal, Perez says the episode has left him anxious. And he no longer looks upon police as a force for good.

“I don’t want any contact, ever, with any police officer. I see a police car, I look the other way,” he said. “I see an officer walking around, I go the other direction.”